Life and Death In A Bonus Year

Last December I wrote an essay for The Times about what I wanted to do with my life after I was diagnosed with terminal cancer. Now when I run into friends on the streets of my town, they hug me and tell me I look great. But I can see it in their eyes; what they really want to say is, “Aren’t you dead yet?” (Continue reading)

The enormity of the news didn’t sink in fully, not at first, even after my doctor uttered the words: “I’m sorry, we did find cancer.” My husband, Dave, and I had only the faintest sense that evening that our lives had been hijacked forever.

Early 2014 brought major surgery, then six weeks of chemotherapy and radiation. Eight months later they found cancer again, so it was Christmas surgery and more of the same. When a scan in June showed new tumors, the outlook turned bleak. The cancer, a rare type — metastatic squamous cell head and neck carcinoma of unknown primary — had gone systemic. (Continue reading)

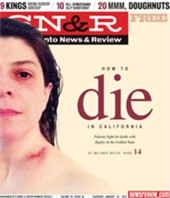

The call comes on your cell when you least expect it, while in line for coffee at Peet’s in Midtown… “The telephone isn’t the ideal way to deliver test results, but …” You urge the doctor to proceed. So, he tells you about your brain cancer. It has metastasized with a vengeance…Now, you find yourself at a new stage, with six months to live. You’re aware that people who die with your disease may face distressing events before the end: seizures, loss of functions, dementia, anguish and undeniable pain. What are your options in the above hypothetical? (Continue reading)

Doctors’ secret for how to die right

My friend, the late poet Diane Callum, wrote a cover story for SN&R back in 1994 that described her journey through diagnosis and into treatment, at age 50, for ductal cell carcinoma, stage 4. In “Breast cancer diary,” she shared with our readers her passion, her anger, the fight she staged against that dreaded disease. (Continue reading)

Sometimes the death of a loved one comes in an instant. But often it takes a slow drain of the calendar to get to the end. In these cases, the family endures while the dying one suffers physical hell mixed with periods of lucidity, joy, even wisdom. So it was for my brother Marty. (Continue reading)

There’s no way to start but with the truth about Marty.

In the spring of 2004, my brother, a medical doctor living near Placerville, began experiencing symptoms of a neurological disorder. He couldn’t make his fingers move in certain rapid alternating patterns—couldn’t tap his thumb to his ring finger, index finger, and so on, as fast as normal. After multiple tests and a process of elimination, my brother diagnosed himself with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, better known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. (Continue reading)

About nine months ago, I wrote a story for SN&R about my brother Marty Welsh, a local doctor diagnosed in 2004 with a terminal illness called amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a.k.a. Lou Gehrig’s disease. Over about five years, the body of an ALS patient becomes paralyzed, with one muscle group after another (hands, arms, legs) ceasing to function. While the process unfolds in the body, the brain continues to thrive.

(Continue reading)

In the fall of 2008, I was sitting around the breakfast table with my brother, a local doctor who was dying from Lou Gehrig’s disease. By that time, Marty, 53, was confined to a wheelchair, could no longer use his legs or arms, plus it was getting difficult for him to speak. I’d stayed overnight at his home to help out; we sat facing each other the next morning over bowls of oatmeal.

(Continue reading)