Six days in D.C.

The nation’s capital is a great place for a tutorial in democracy. Too bad America won’t take a lesson.

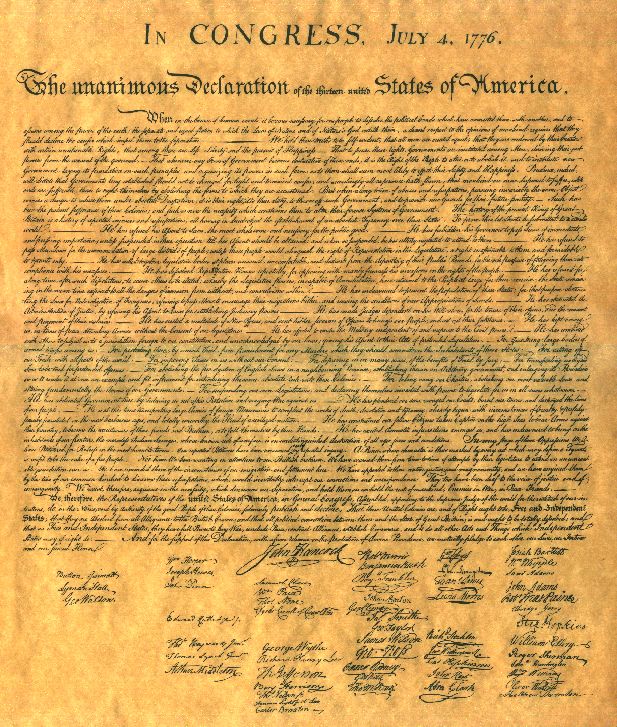

As throwback as it sounds, I’d always been thrilled by the words put down there: the “we hold these truths,” the “unalienable rights,” the desire to submit facts to a “candid world.” Especially moving, of course, was the part where Thomas Jefferson explains why it’s the duty of the people to throw off a government when it turns destructive or betrays its purpose.

So it wasn’t long after leaving Sacramento and arriving in Washington, D.C., for the first time that I found myself climbing the steps of the National Archives in search of the Declaration of Independence. I entered the Rotunda and walked straight up to the document, displayed behind bullet-proof glass—just like Nicolas Cage told us about in National Treasure.

Unlike the U.S. Constitution, which rests nearby, the Declaration and its incendiary content turn out to be barely legible to the naked eye, despite attempts at restoration. All I could make out was “When in the course of human events …” before the words faded away to nearly invisible.

The experience choked me up, anyway. The contrast between the integrity of this founding message and the lack of decency with which America operates on the world stage today is glaring and scary. It’s as if the country’s ambitions as a democracy turned inside out somewhere along the way, especially this last decade. Much of this is due to a regularly reviewed litany of wrongs, including a ludicrous war, an arrogant administration that holds itself above the law, and a government that can’t seem to solve fundamental problems (i.e. a gravely threatening climate crisis; a bankrupt health-care system; a racially divided, inner-city public education system; a badly wounded economy; etc.).

The uneasy contrast between the ideals and the reality festered throughout my stay in D.C.

Over the course of my six days there, I wandered the halls of the nation’s Capitol, the Library of Congress, the Supreme Court, and the Smithsonian with its bounty of museums and gardens. Despite plenty of arcane traditions and notions, I marveled at the cool nobility of the democratic ideals presented. The monuments took this message further home. The Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial reminded that it was the people, not the politicians, who ultimately ended that war. And the Franklin D. Roosevelt Memorial, with its waterfalls and bronze, reminded that it was inspired leadership that helped regular citizens rebuild the country and overcome the dark times of the Great Depression.

Toward the end of the D.C. visit, my friends and I climbed the wide steps of the magnificent Lincoln Memorial. We turned on the open landing halfway up to the seated statue and faced the reflecting pool and towering Washington Monument in the distance. We were standing on the spot where Martin Luther King Jr. spoke to the throngs of civil-rights protesters at the March on Washington in 1963, the place where he famously told the country, simply and astoundingly, that he’d had a dream.

It struck me, there and then, how compatible his dream was with the evolving notion of democracy Jefferson had written about in the document I found beneath the bullet-proof glass in the National Archives. Flying home to Sacramento on the seventh day, I worried about what was next for our democracy and who would carry that dream.