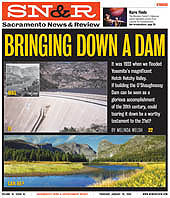

Bringing down a dam

Hetch Hetchy was once magnificent, unspoiled wild land. It could have the same splendor as its neighbor, Yosemite Valley, with the help of a grad student and a dam demolition.

Consider for a moment that you live in a world that builds improbable things like this enormous, sloping water gate in this most spectacular of settings deep in the forests of Yosemite National Park. The O’Shaughnessy Dam—with its magnificent arch of concrete, curved inward like an enormous white punch bowl—was thought in its day to be a marvel of industry, a covenant with progress. It didn’t arrive here in this remote place because of a miracle. You just decided to build it.

Now face north toward the Wapama Falls. See its waters crashing 1,800 feet from granite cliffs above into the inviolable reservoir below. Look just this side of the glaciated cliffs, also to the north, and find the white waters of the Tueeulala Falls cascading into that same vast pool. You are looking at the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, beautiful and cold. Don’t touch its waters; don’t go near its protected shores. You are not allowed. This is water for drinking, and it’s off-limits for recreational uses.

As you now gaze to the east from on top of the dam, to the snow-capped Yosemite peaks that rise over this place where the Tuolumne River once flowed, you can imagine that a Rivendell-like valley once could be found here. History tells us it was flooded under 300 feet of water in 1923 when the dam was built to assure clean drinking water for the people of San Francisco—a city still shrouded in the lingering effects of the firestorms of the great earthquake of 1906.

Not even the famous conservationist John Muir could mount a campaign strong enough to save the valley.

Now a century has passed, and humankind has made myriad improvements in water-supply systems and drinking-water technology. Although no one can deny that this reservoir has, for the past eight decades, provided reliable drinking water to much of the Bay Area, it is a simple truism that the O’Shaughnessy Dam would not be built if it were proposed today. It would be vastly more controversial and, in any case, mighty expensive to construct.

As you stand on the gigantic wall now, however, the dam seems timeless, utterly permanent. In fact, it’s impossible to imagine things were ever any different or that Hetch Hetchy will ever be any other way.

But a wind has shifted; a very different idea has taken hold. Scientists and environmentalists have put forth convincing evidence this past year that the dam could be demolished and the Hetch Hetchy Valley restored without losing a drop of water supply. There are other options for storage, reasonable alternatives. The problem is one of politics, they say, not engineering. Indeed, if the many obstacles to removing the dam could be overcome, a stunningly beautiful valley—one Muir called “a mountain temple”—slowly could repair itself here as you and visitors from around the world paid witness.

So today, like in Muir’s day, Hetch Hetchy has become a subject of striking controversy again—pitting science against politics, valley against city, nature against industry.

Question: If building the O’Shaughnessy Dam can be seen as a magnificent accomplishment of the 20th century, could tearing it down be a worthy testament to the 21st?

There are those who believe the answer is yes. Perhaps you are one of them. And perhaps you also can believe—like in J.R.R. Tolkien’s books—that even the smallest person might play a part in changing the lost valley’s future.

Sarah Null wears the uniform of an average graduate student: jeans, slouching sweater and tennis shoes. But Null—who looks younger than her 29 years, with shoulder-length brown hair and clear blue eyes—is far from an average student. Last year, she wrote what likely has become the most widely read master’s thesis to come out of UC Davis in decades. Her topic was Hetch Hetchy and the implications of removing the O’Shaughnessy Dam.

If science runs in the genes, then perhaps Null’s parents, a zoologist mom and a biologist dad, had something to do with her choice of vocations. Raised in a small town in the San Gabriel Mountains of Southern California, Null received her bachelor’s degree at the University of California at Los Angeles and then went to work for the U.S. Forest Service at Mono Lake. She led hikes and gave tours of the lake and Sierras when the weather was good. When it turned cold, Null—an outdoor-sports devotee—would join the ski patrol in Mammoth.

In 2000, she moved to Davis and began graduate work, taking classes in engineering, hydrology, geography and ecology. A focused student, she found she had a skill for solving problems, for scrutinizing numbers and comprehending the meaning hidden in them. Soon, Null was introduced to a computer water-modeling program called CALVIN, which spit out mounds of data on water in California. Null learned that CALVIN could take vast amounts of information—such as 72 years of river-flow data from the Sierra Nevada—and sort it in ways that made it possible to examine problems in brand-new ways.

CALVIN’s inventor turned out to be Null’s graduate adviser, Jay Lund, a leading California water scholar and an 18-year UC Davis professor of civil and environmental engineering. The potential applications for CALVIN were substantial, as the program could utilize economic and engineering data on water-supply systems all over the state. Lund had the idea that someone should use CALVIN to study Hetch Hetchy. “I was looking for a promising master’s student,” he said laughing, “… a little bit brave, a little bit quirky.” He found Null.

The graduate student’s path of investigation was set. Much of the water data for the Sierra region was loaded into CALVIN already, so it was only a matter of months before she was able to ask it simple questions, especially this one: What would happen if you took away the O’Shaughnessy Dam?

The answer was revealed to Null over the course of a year, on a scrolling screen, in vertical columns of millions of matrix-like, flowing numbers. She’d load variables into the computer and return sometimes five to eight hours later, once CALVIN was finished sorting. After that, when the data had been sifted in particular ways, she’d examine the numbers in search of answers to questions like these: How much extra capacity is there in downstream reservoirs? What happens in wet years? In drought years?

Within a few months, she and Lund had discovered a stunning result: CALVIN showed that removing the dam would take no water out of the system—you just have to store it differently. Basically, a pipeline “inter-tie” between the Hetch Hetchy aqueduct and the much larger New Don Pedro Reservoir (six times the size of Hetch Hetchy Reservoir) would allow almost all of the water now captured at O’Shaughnessy Dam to be arrested downstream instead. It became clear that there was huge flexibility in the system. Both the graduate student and her professor had expected the Hetch Hetchy- without-a-dam solution to be complicated. “We were expecting to have to do something fancy,” said Null. “It turned out to be blissfully simple,” agreed Lund.

Still, both were quite aware of the study’s limitations—i.e., the scientific solution on Hetch Hetchy might be simple, but the politics were utterly complicated.

Later that year, Null presented preliminary findings at a water-engineering confab that was held at Asilomar in Monterey County. “It was my first conference,” said Null. “I was terrified.” She gave her presentation and received what she thought was polite appreciation from those attending. But some people, like Ron Good of a Sierra Club break-off group called Restore Hetch Hetchy, had heard of Null’s work and traveled a long way to hear her early results. Good, who’d had no prior contact with Null, found her report “thrilling” because it mirrored similar, but as yet unpublished, modeling research that had been undertaken by other Hetch Hetchy-restoration allies at Environmental Defense, a national nonprofit group.

A few months after Asilomar, Null’s completed thesis, “Re-Assembling Hetch Hetchy: Water Supply Implications of Removing O’Shaughnessy Dam,” was completed. A smattering of newspaper articles came out on it. Null was pleasantly surprised. “I thought, ‘Oh, this is really neat.’ … It’s easy to think your thesis will get filed away somewhere and that no one else will ever read it besides your three committee members.”

Lund, who knew the controversial topic of Hetch Hetchy would make Null’s findings an intriguing subject to the press and public, nonetheless was unprepared for the controversy that was to come. “I expected more attention on this than the average thesis,” he admitted, laughing. “But I had no idea … I still don’t know when it will end.”

Good speaks the earnest language of a true believer. “The spirits have been with us!” he said in explanation of the sweep of events this past year that he thinks have brought the dream of a restored Hetch Hetchy Valley closer to reality. He talks about the spirits with a smile, but he clearly believes fate has played a role in what’s been happening. “Why did Sarah Null pick Hetch Hetchy as an issue?” he mused. “It just happened out of the blue!”

A 25-year card-carrying member of the Sierra Club, Good had spent time on staff with that organization back in 1987, when then President Ronald Reagan’s interior secretary, Donald Hodel, surprised the nation, especially the part that resides in the Bay Area, by suggesting the scrapping of the O’Shaughnessy Dam. Hodel had come to believe that a second visitor attraction in Yosemite National Park would enhance the park system and ease pressure on the overcrowded Yosemite Valley. This was the first time since the Raker Act of 1913—when Congress gave San Francisco the right to build the dam—that anyone had mounted a serious challenge to the dam. But the Hodel bid went nowhere, with vehement opposition being led by former San Francisco Mayor and now Senator Dianne Feinstein, who once dismissed Hetch Hetchy as “a campground.”

But, by then, the dream of a restored Hetch Hetchy (Miwok for “grass seed valley”) had seeped into Good’s bones. He knew that the flooded valley would look, at first, like a moonscape after the dam was drained. But restoration experts were certain that soon flourishing meadows would surround the wild Tuolumne River as it returned to its natural channel. As reseeding of the habitat proceeded—whether naturally or aided by ecologists—the valley’s lush groves of ponderosa pine and black oak slowly would return. Willow and alder trees would begin to grow up along the river. “People will be drawn from all over the world to witness the process. It’s evolution,” said Good.

With this dream in mind, Good moved to Sonora near Yosemite National Park and set up a Sierra Club task force to look into the issue. In 1999, the organization went independent as Restore Hetch Hetchy and began to raise its own funds. By 2001, the group hired Good as director. The title of its platform statement speaks for itself: “The Hetchysburg Address,” which quotes Muir (“Earth has no sorrow that Earth cannot heal”) and calls for “giving birth to a restored Hetch Hetchy Valley.”

Good knew that people get most passionate about saving the environment if they’ve spent time in it themselves, so he knew that taking opinion leaders out to Hetch Hetchy would be a positive thing. “Let the waterfalls speak to the powerful,” he said. About a half-year after Null’s thesis was released, Good got an unanticipated e-mail from Tom Philp, an associate editor at The Sacramento Bee. Philp, who had interviewed him about Hetch Hetchy back in 2002, asked Good if he’d be willing to accompany him on a July hike around the dam. “I thought about it for a millisecond,” said Good, laughing.

Good met Philp, who writes for the Bee’s opinion sections, at the Evergreen Lodge just outside the valley, and the pair drove together to the O’Shaughnessy Dam. They walked out onto the bowed stretch of concrete that holds back the waters of the reservoir and took in the beautiful stillness of the forbidden water body. They gazed south at Kolona Rock, a steep granite precipice that guards the valley, and saw the crashing Wapama Falls. The activist and the journalist crossed through the enormous granite tunnel on the far side of the dam and took off hiking toward the falls.

“We chatted; we dreamed a bit,” said Good about his trek with Philp. And then, with a chuckle, “I think the waterfall spoke to him.”

Perhaps it did. About a month after the hike, Philp let loose with a surprising and relentless barrage of editorials and articles in the Bee about the restoration of the Hetch Hetchy Valley. As it turned out, Philp had been following the issue for the past year and had decided to join Good on a hike as a sort of “gut check” on whether or not to proceed with the series he had pitched to the Bee’s editorial board. “I had to reassure myself that this place was beautiful,” he said. Several of the pieces that came out cited Null’s work, in what was referred to as a UC Davis study or research by UC Davis scientists. One article, on August 29, was an interview Philp conducted with Null and Lund about CALVIN and their findings. In total, the Bee wrote a series of 12 editorials and articles from August 12, 2004, through the end of September.

One editorial, “San Francisco’s paradox,” talked about that city’s “great civic contradiction” for pushing a global environmental agenda when all the while “it keeps a glacial valley locked away close to home.” Another time, Philp conducted an imaginative fictional interview with Muir, drawing from the writings of the famous environmentalist.

“I thought, ‘Wow. This is great!’” said Good about the fusillade of attention coming from the Bee. “There was another one, and another one!” Perhaps Philp was unconsciously channeling The New York Times circa 1913, when that paper wrote a series of six thunderous editorials opposing the O’Shaughnessy Dam when it was before Congress, urging then President Woodrow Wilson to stop the San Francisco “water grabbers.”

Something else happened in September, too. Environmental Defense captured headlines across the country with its new Hetch Hetchy-engineering report, “Paradise Regained.” Respected consulting firms and scientists with expertise in water, engineering, water law and environmental planning conducted research for the report. And some of the findings were very familiar.

As with Null’s thesis, this study found that the dam could be removed without threatening state water supplies. “Paradise Regained,” which detailed somewhat different plans for how to replace Hetch Hetchy’s water storage and electricity production, estimated that the cost to expand water-storage facilities below Hetch Hetchy (minus the cost of actually dismantling the dam) would be between $500 million and $1.6 billion. Now was the perfect time to look again at Hetch Hetchy, wrote the report’s authors, since San Francisco was getting ready to spend $3.6 billion on an upgrade of its entire water system.

It should come as no surprise that all of the above drew the wrath of the people who want the dam to stay put. Launching a mini media war, the San Francisco Chronicle published an editorial, “The Hetch Hetchy fantasy,” that dubbed restoration of the valley “an inspiring goal” but basically ridiculous. “This is no time to destroy an important source of water,” wrote the editors. “It’s easy to look back and declare O’Shaughnessy Dam a mistake. It’s impossible to look forward, however, and not recognize that tearing it down could be an even greater error.”

In a more caustic piece, Chronicle columnist Ken Garcia took a stab at the Bee, claiming that “a lot of hot air” was coming from Sacramento these days, but, surprisingly enough, it wasn’t coming from the Capitol. It was coming from the Bee, he wrote, in “what could charitably be called an intellectual exercise.” He labeled the Bee’s campaign “all washed up” in its effort to pound away at “snobby San Francisco.”

Even the hypothetical removal of the O’Shaughnessy Dam comes with complexities too numerous to count. Multiple and overlapping federal, state and local governments have their hands in Hetch Hetchy and the Tuolumne River on issues involving everything from land use to water storage to electricity rights to flood control to earthquake safety. Importantly, the downstream water rights on the Tuolumne are intertwined—by federal law—with the Modesto and Turlock irrigation districts.

But since the 1913 law guaranteed San Francisco certain crucial rights to Hetch Hetchy’s water, the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC) seems to be the major player. When visitors drive to Hetch Hetchy’s gate, they receive an elaborate color brochure detailing the operation of SFPUC’s water system, which serves 2.4 million people—more than one-third of the population of the Bay Area—with its pipelines and tunnels carrying pristine water 160 miles from Yosemite National Park to the Bay Area. Some 85 percent of San Francisco’s drinking-water needs—plus most of those of San Mateo, Santa Clara and Alameda counties—are quenched through these corridors.

“My responsibility is to guarantee high-quality drinking water to close to 2.5 million people,” said Susan Leal, director of the SFPUC, “and I will oppose any proposal that puts that responsibility at risk.” Tony Winnicker, communications director for the agency, characterized the Environmental Defense study as painting a “rosy scenario” that “vastly underestimated” the cost—actually in the billions—that would be involved in such an undertaking. Theory is fine, he said, but the SFPUC lives in the real world, where practical, legal, financial and political realities make the city’s need for the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir clear. “It’s fine to study this,” he said. “But [removing the dam] is very far, very distant from ever becoming a reality.” He stated that Null’s thesis was “simplistic modeling” that didn’t address the complexities of the issue.

Both Leal and Winnicker expressed an opinion that the politically savvy people at Environmental Defense were responsible for much of the recent momentum on the Hetch Hetchy-restoration issue. “For the first time, a well-funded, sophisticated national organization has placed this issue as one of their priorities,” Winnicker said. The agency would prefer to view the recent impetus around Hetch Hetchy as orchestrated by Environmental Defense rather than consider it the result of a series of fortuitous events for restoration proponents.

As for the irrigation districts, they hold “senior” rights to the downstream river waters, despite the fact that they get neither irrigation nor drinking water from the reservoir. However, as part of the 1913 law, San Francisco promised to sell surplus electricity generated at Hetch Hetchy to the irrigation districts at cost. Although they use only a fraction of that energy today, it remains a cheap source of power for them.

Larry Weis, general manager of the Turlock Irrigation District, is skeptical, to say the least, about any moves against the dam. “We had better improve water storage, not erode it,” he said. As for the idea that the New Don Pedro Reservoir had plenty of extra capacity to capture and hold water in lieu of the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, Weis said it’s not true. That’s partly because that reservoir provides flood-control protection for the Tuolumne watershed.

Restoration obviously has powerful opponents in San Francisco’s political and business circles, as well, with Feinstein usually throwing the first punch in any Hetch Hetchy brawl. The Bay Area Council, a business group that represents the nine-county region’s major employers, is flat-out opposed to any further study of the matter. San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom told the press in September that he needed to look into the issue further. But he also recently told constituents, “We are going to fight to keep Hetch Hetchy in the city’s hands.”

You’d think nothing could surprise Null at this point. Her work had made her a kind of low-key student celebrity on and off campus, with some singing her praises and others dismissing her work. Null tried not to take any of it personally, instead fixing herself on a next goal: attaining her Ph.D. and writing her dissertation on a subject completely unrelated to Hetch Hetchy.

Still, she was startled when Assemblywoman Lois Wolk invited her and Lund to a Capitol briefing on Hetch Hetchy. Wolk had decided the time was right to take the subject up within the Legislature. In September, she convinced another state leader on water issues, Assemblyman Joseph Canciamilla, to co-write a letter to Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, asking his administration to support a state-sanctioned study of Hetch Hetchy.

In November, Null and Lund joined Good and representatives from Environmental Defense, the SFPUC and the irrigation districts at a packed legislative briefing on Hetch Hetchy at the state Capitol. Good expected fireworks from the irrigation-district people, who, he said, had made public statements dismissing Null’s report “like it was a little junior-high homework assignment.” Good said no sparks ensued at the briefing, with the creditable Dr. Lund backing his student up. “I mean, Jay Lund is a water guru for the whole state!” Nobody seemed to want to take him on, at least at that particular meeting.

A few days later, an unexpected thing happened: The governor said yes. In a written response to the two legislators, Schwarzenegger’s Resources Agency secretary, Mike Chrisman, wrote that he would direct the Department of Water Resources to review the last 20 years’ worth of restoration proposals, including “Paradise Regained” and Null’s thesis. Needless to say, his letter was greeted with praise by environmental groups.

“The recent studies suggested it was time to take another look,” Chrisman told SN&R. He revealed that Schwarzenegger himself determined that Hetch Hetchy was a worthy subject to examine. Chrisman insisted that the undertaking would not constitute a “new study” but would consist of a state-sponsored “gathering of information” from studies that have been accomplished already. “Our goal is to create a framework for an informed public dialogue,” he said. Born and raised in Visalia, Chrisman grew up in the Sierras and said he knew Hetch Hetchy well.

In about a year, the state report should be complete. Chrisman said he had no idea what might happen after that. “The Legislature might want to hold hearings,” he postulated.

Also in the future: Two books on the Hetch Hetchy controversy are slated for publication this spring. And the group Restore Hetch Hetchy has a study coming out in late February that, among other things, will examine how a restoration process might proceed—i.e., how does one best deal with 2,000 acres of denuded terrain?

Some suggest that the Hetch Hetchy issue is ready-made for a governor who wants to make sweeping statements and grand gestures. “Bring me big ideas,” said Schwarzenegger in his recent State of the State address. Many think restoration of the Hetch Hetchy Valley could be just the kind of environmental splash he’s looking for. Although it would take about $100 million to bring down the dam and 100 years to completely restore the valley, the political capital in undertaking such a thing, at least nationally, might be more immediate. After all, a Hetch Hetchy-reclamation drive would commence the greatest wild-lands restoration project ever attempted in the history of humankind.

It’s interesting to note that Lund doesn’t even consider himself an environmentalist. “Just as much as your average person,” he said, shrugging without guile. A heartfelt academic, the man who created CALVIN has never even been to Hetch Hetchy.

But his most famous student, Null, has been there. She has stood on the O’Shaughnessy Dam, stared at the silent reservoir and walked the trail past the Tueeulala and Wapama falls. She recently hiked the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne, a famous trek that follows the river as it descends within a few miles from the Tuolumne Meadows almost 5,000 feet to the Hetch Hetchy Valley below. The river flows over granite shelves and then crashes over precipitous waterfalls. At the dramatic Waterwheels, granite boulders in the riverbed launch arcs of white water 40 feet into the air. Someday, visitors from around the globe might have the ability to better access such spectacles of nature on the trails above Hetch Hetchy. Yes, and they also might have the chance to stroll through the valley beneath and witness the rebirth of what Muir called “the wonderfully exact counterpart” to Yosemite Valley.

But last spring, up along the high trail, Null gazed down at the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir below without any such thoughts. The graduate student wasn’t entertaining grand notions about the future and how her thesis might end up as part of a sweep of events that could restore the magnificent valley. An academic at heart, with a deep love of the wilderness, Null was just grateful to be there, on a mountain, in the moment.