The call comes on your cell when you least expect it, while in line for coffee at Peet’s in Midtown. The doctor, a specialist from out of town, says “The telephone isn’t the ideal way to deliver test results, but …” You urge him to proceed. So, he tells you about your brain cancer. It has metastasized with a vengeance. His words are both shocking and anticipated. You know you are hearing your own death sentence. You have fought valiantly for years to be rid of this disease. You’ve endured the onslaught of surgery, radiation, chemotherapy. Your loved ones rallied in support. You’ve done everything you can to continue living fully. Now, you find yourself at a new stage, with six months to live. You’re aware that people who die with your disease may face distressing events before the end: seizures, loss of functions, dementia, anguish and undeniable pain. What are your options in the above hypothetical? In California, you could choose ever-more-aggressive interventions in the unlikely hope of a cure. You could greenlight a medical trial and perhaps extend your life, and aid science. You could choose palliative care and hospice, in the unassailable theory they may provide you a gentler exit. You could even exercise your right to refuse food and drink, a difficult path that leads to death in seven to 10 days. Or you could move to Oregon. There, you would have an extra option. You could choose to end your own life, at the time and in the place of your choosing, with legally prescribed, fast-acting barbiturates provided by a doctor. As of right now, this final option is illegal in California. In fact, your loved ones could face criminal prosecution for aiding you in pursuit of it here. But all this may be changing. Just this week, Davis-based state Sen. Lois Wolk announced legislation that would bring an “end-of-life choices” law to California. The law would be fundamentally like Oregon’s 1997 Death With Dignity Act—requiring an adult patient to have residency in the state and two doctors in agreement that he or she has less than six months to live and full mental competency. Other safeguards Wolk referred to as “crucial”—for both patients and physicians—will also be folded in. “It’s time,” she said. “No one should have to go through horrific pain and prolonged suffering when the end is clear.” A longtime advocate for more compassionate end-of-life scenarios, Wolk authored a groundbreaking 2008 law that provides seriously ill patients with a new mechanism—Physicians Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment, or POLST—to ensure that their wishes are honored regarding end-of-life care. But Wolk, the state senate’s new majority whip, will likely face a tough battle this time. The right-to-die subject has been exceedingly controversial when it’s come up in California’s past. So why introduce it now? Because of Brittany Maynard, the 29-year-old East Bay newlywed who, diagnosed with late-stage brain cancer (glioblastoma multiforme) last spring, became the face of a movement when she chose to relocate with her husband to Oregon so as to end her life under that state’s Death With Dignity Act. “Doctors prescribed full brain radiation,” she wrote in an essay for CNN. “The hair on my scalp would have been singed off. My scalp would be left covered with first-degree burns. … My family and I reached a heartbreaking conclusion: There is no treatment that would save my life, and the recommended treatments would have destroyed the time I had left.” Young, attractive and articulate, Maynard’s passionate defense of her right to leave life on her own terms went viral. Her YouTube video drew 13 million views. Her saga was written up in hundreds of newspapers and appeared on the cover of People magazine. Maynard partnered with the nation’s premier “aid in dying” nonprofit, the Denver-based Compassion & Choices, and triggered an outpouring of new energy and funds to its cause. Ultimately, the sympathy generated by Maynard’s story pushed the Death With Dignity movement forward in ways the country is just starting to see play out. A month after Maynard’s November death, the already substantial public support for Death with Dignity took a significant bounce. A Harris Poll found that 74 percent of American adults now believe terminally ill patients in great pain should have the right to bring their lives to a close. Even “physician-assisted suicide”—a term controversial in right-to-die circles—now has a 72-percent favorable rating. “I think [Brittany Maynard] deserves a lot of credit for being willing to be so public about her dying,” said Wolk, who said the young woman’s story was “very much” part of why she and co-author state Senator Bill Monning chose to introduce legislation now instead of later. “People were very moved by her story,” said Wolk. “It struck a chord. “To be forced to set up residency outside California to relieve yourself from suffering? That’s not right.” ‘Things can go really wrong’ With her short brown hair, eloquent eyes and gracious smile, Jennifer Glass welcomed a rain-soaked reporter into her San Mateo home last month, ushered her to a seat in front of a cozy fire by the Christmas tree, and handed over a cup of steaming coffee. The warm environs seemed to alleviate the difficulty in speaking openly about the topic at hand: Glass’ late-stage lung cancer and statistically probable decline, and death, from the disease. A formidable communications professional during her working career—with stints at Oracle, Intuit, Sony and Facebook—Glass married the man of her dreams, Harlan Seymour, in August of 2012. They settled into family life. Four months later, while giving her a back rub, Seymour found a lump on her neck that felt “like little peas in a row.” Glass was soon discovered to have Stage IIIB lung cancer (not smoking related) that had metastasized to the lymph nodes in her neck. At the time of her diagnosis, the American Cancer Society estimated the likelihood of her five-year survival rate at just 5 percent. The then 49-year-old underwent radiation and two aggressive rounds of chemotherapy, causing her to lose her thick brown hair. Her cancer is, thankfully, now in a period of “treated containment.” She takes the oral chemotherapy drug Tarceva daily that allows “two to three good hours” per day, she says. The efficacy of Tarceva tends to be two-to-four years before cancer mutates around it. Glass, who developed a following for her YouTube video “A Photo a Day: One Year with Cancer” and for blogging about her disease on The Huffington Post, has strong beliefs about how she wants to go when her time comes. “I believe I should have the legal choice to end my life calmly, peacefully and with dignity,” she said. Like Maynard, the tech-savvy Glass wants to bring the right-to-die debate to a generation that’s become accustomed to making its own choices when it comes to certain issues. “It’s like what we’ve seen with gay marriage,” she said referring to the sea change in public opinion and policy on that issue in a short time span. “There’s a greater desire for personal choice … and quality of life. And that has to include end of life.” When first diagnosed, Glass contacted Compassion & Choices—which was responsible for creating and passing Oregon’s Death With Dignity Act 17 years ago. She sought advice and counsel. A volunteer came to her home and explained advance-care directives, POLST forms, the role of hospice and what was and wasn’t legal in California when it comes to the end of life. Glass, who had been an advocate on the right-to-die issue even before her diagnosis, was thankful to have that information going into the physical and emotional fight of her life. After her marathon cancer treatment was completed, Glass contacted Compassion & Choices a second time and asked how she could help their effort to make aid in dying legal in California. She is unapologetic when explaining why hospice and palliative care alone are not sufficient to calm her fears about the possibility of dying in pain or discomfort. “There is some exceptionally fine hospice care,” she said, “but it’s a spectrum. Sometimes it’s simply not possible to eliminate or manage a dying person’s pain.” People like Glass don’t much like the word suicide—as in “physician-assisted suicide”—imprinted over the right-to-die option. Suicidal people are sad or depressed and want to die, she said. “I’m doing everything I can to live! But I want control over my death if it’s going to go in a really ugly way.” She and others suggest “aid in dying” or “death with dignity” as alternative word choices to “physician-assisted suicide.” Glass admitted to a kind of black market that exists in states where physician-assisted dying is illegal. “Since becoming part of the cancer community, I’ve known people who are doing whatever they think it’s going to take to end their lives when they want to, including hoarding pills. That can be dangerous if it’s not managed. “It’s the fear, the fear about how this is going to end.” In her own case, Glass is frightened by the possibility she may be forced to “drown in my own lung fluid in front of my family in my final days. … My quality of life in whatever time I have left would be vastly improved if I knew [a legally prescribed lethal drug] was an option for me under the law. “If my life is not tolerable, if I’m wracked with pain, if I can’t control my functions, if my system is failing … and I have no recourse? That’s the worst thing I can think of. Because things can go really wrong.” If her disease runs its course, Glass says she knows what it would take to move to Oregon and, like Maynard, take the steps necessary to be approved for self-administration of a lethal prescription. “But I really hope it doesn’t come to a decision where I have to leave my home,” she said. “Particularly because if it comes to that, it’s a decision I’m going to have to make when I’m already very sick.” ‘A personal, intense experience with dying’ Toni Broaddus entered Café Bernardo near the Capitol on K Street, primed for her first in a long string of meetings scheduled that day with legislators, staffers and local officials. It was November 19, 2014—the date would have marked Brittany Maynard’s 30th birthday. “Brittany’s story really galvanized the movement,” said Broaddus, an attorney and social-justice advocate who now directs the Compassion & Choices campaign in California. “Her story has really moved us forward in ways we never could have predicted or expected. We have seen a huge increase in supporters, in donors, in volunteers.” Broaddus, previously a leader in the state’s marriage-equality movement, said Compassion & Choices has set a goal of having California join the five other states in the country—Oregon, Washington, Montana, Vermont and New Mexico—that have legalized aid in dying. The group plans to assist in the passage of California legislation or mount a grassroots effort to get the matter put before voters in 2016. Such efforts have failed in the past, however. Attempts to legalize assisted dying in California have been beaten back many times over, thanks to fierce opposition from organizations like the Catholic Church, with its moral authority, and the California Medical Association, with its well-financed lobby. In 1992, the statewide ballot measure Proposition 161 went down with 46 percent of the vote. The most recent legislative attempt, Assembly Bill 374 by Assemblywoman Patty Berg, was taken off the table for lack of support at the end of the 2007 session. Famously, the bill had preachers speaking out in opposition from the pulpits in California. Then-Assembly speaker, Fabian Nunez, actually described getting a call from his churchgoing mother at that time, urging him to reconsider his support for the bill. The powerful California Medical Association is predicted to oppose again this time, though a spokesperson said the group hadn’t yet taken a position on new legislation. The organization, which officially represents just 30 percent of the state’s physicians, has claimed before that assisting in a death is in conflict with a doctor’s ethical responsibility to “do no harm.” Also, the doctors’ group holds that most pain at the end of life can be controlled through medication and comfort care in a hospice environment. However, a recent poll of 17,000 American doctors by Medscape, for the first time, found physicians supporting death with dignity for those with “incurable and terminal” disease by a 54-percent majority. Also expected to oppose Wolk’s legislation are some in the disability-rights community, who say such a law could open up the potential for abuse by insurers or family members. Patients might be pushed to an early death for the convenience of others, they say. In response to the groundswell of media on Maynard’s story, Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund senior policy analyst Marilyn Golden wrote: “For every case such as [hers] there are hundreds—or thousands—more people who could be significantly harmed if assisted suicide is legal.” Broaddus disagrees, based on 17 years of data from California’s neighbor to the north. “People talk about concerns about abuse for vulnerable populations,” she said. “But the reality is, that hasn’t happened in Oregon.” For her, California’s lack of a law simply doesn’t make sense. “It’s hard to understand given the support in the state and the state’s usual leading role on this kind of social-justice issue.” For Assemblywoman Wolk, the fate of the bill will depend, in part, on individual legislators’ own personal experiences with death and dying. “More and more people have had a personal, intense experience with dying—either a relative or a friend … and they want it to be different, they know it should be different,” she said. The legislator pointed out that the Oregon law “is broadly accepted and not that heavily used,” with about 60 percent of the people who obtain a prescription ever actually taking it. “It’s a comfort for people to know that if it got really bad, it’s there,” she said. “That seems to make people feel better. Just having it is enough.” ‘You’re scared and stressed’ Barbara and Doug Wilson met in 1967 while residents in UC Davis’ first co-ed dorms. They fell in love, married, launched careers and raised two daughters, never once leaving the safe haven provided them by the city of Davis. How could the couple have known that security was fleeting, that they were not destined to accompany each other into their elder years? In 2004, Doug, age 57, was diagnosed with Stage IV colon cancer. At first—thanks to two rounds of surgery and chemotherapy—his disease went into remission. But in 2007, the cancer returned. With Barbara constantly at his side, he spent the next five-plus years in and out of infusion rooms, clinics, radiation centers and hospitals undertaking every treatment and intervention doctors recommended to help save his life. “He was amazing,” said Barbara of her husband. “He had the most positive attitude. He did not want to die.” But eventually, in the spring of 2013, the couple chose to enter hospice care, more than anything because it would get them access to equipment—like a battery-operated oxygen tank—that would help Wilson attend his daughter’s April wedding in Santa Cruz. “Doug walked my daughter down the aisle,” said Barbara, choking back tears. On morphine for pain, he gave his father-of-the-bride speech and, she said, “did the father-daughter dance.” By the following Friday, he was gone. Barbara, now 66, looks back with disquiet and some unease on her husband’s death process those last five days of his life. “The image of a wonderful, peaceful end of life with loved ones around … well, that didn’t seem to happen,” she said. Home hospice provided qualified people checking in once a day, she said, and availability in emergencies. But basically, she felt left to her own resources, in the company of her two daughters and son-in-law, without experience or knowledge in how to attend to a dying loved one. “I think it’d be the same with any hospice,” she said. “You’re scared and stressed because this is your loved one,” she said. “You don’t know what to do.” She described her husband as on-again, off-again agitated—he was bleeding internally, with his liver shutting down. “We felt we were incapable of dealing with him properly,” she said. She described frustration at her inability to help make him comfortable. She feared his pain and what would happen if she gave him too much or too little morphine. Eventually, in a hospital bed in the living room with his family surrounding him, her husband took his last breath. But the day-by-day countdown to Wilson’s end remains a fairly traumatic memory for his beloved wife. The Wilsons’ story illuminates the reality that the actual process of dying can take time and be upsetting, confusing and painful for both patient and caregivers, especially those who are facing death’s tests for the first time. Though Barbara believes her husband would not have chosen to take his own life at the end even if it had been legal, she now personally believes that people should have a right to that option. “Until you walk in those shoes, you just don’t know. … When it’s my time, I do not want to suffer,” she said, “especially after watching Doug.” Why is it so hard? Why is it so very difficult for modern society—with its medical aptitude, technological advantages and ability to fulfill desires—to succeed at delivering a “good death” when its something most everybody wants? In his recent bestseller Being Mortal, Atul Gawande takes a stab at an answer by laying out the limits of medicine and inadequacies of medical school in preparing physicians to help patients deal with the stark reality of death. Doctors have been trained to find cures and “to win,” he writes. This simple fact—along with an American health-care system that seems to encourage excessive treatment—continues to make a peaceful death an elusive goal for many people. For example: Though most people want to pass away at home surrounded by loved ones, 70 percent die in a hospital, nursing home or long-term-care facility after a long struggle with advanced or incurable disease. Marge Ginsburg, executive director of the Sacramento-based Center for Healthcare Decisions and noted advocate for better end-of-life outcomes, has spent the last two decades pushing for more compassion for patients as they near death. “You’d think 20 years later we’d have gotten this solved,” she said. “But no, we haven’t.” Ginsburg, whose nonprofit organization won’t be taking a position on the new Death With Dignity legislation, reminds that California’s end-of-life problem is much larger in scope than the debate over one potential last-resort option. The importance of advance-care directives and the ongoing push for family members, physicians and patients to have candid conversations before crisis hits can not be overstated, she said. “The ICU is not the time to start finding out what your family members want,” she said. Still, some see a shift occurring in the end-of-life landscape—perhaps because members of an aging baby-boomer population have begun to see their final acts in sight. Indeed, more doctors are now being trained in palliative care, which focuses on pain relief over cures for terminally ill patients. Also, there’s an increased use of advance-care directives and POLST forms as well as an uptick in the number of individuals dying in hospice care. Meanwhile, over to the side, is the more controversial subject of a California law that would allow people who meet its dire criteria to self-administer lethal prescription drugs. Could a shift be occurring there, too? Wolk believes the answer is yes. “It’s changing,” she said. “We have to learn. Doctors have to learn. At the end of life, there is a range of things that can happen. We haven’t wanted to think about that. We haven’t wanted to talk about that. But it’s time.” Those who followed Brittany Maynard’s story this past year—with its tragedy, awareness and resolve—might tend to agree with Wolk that things have to change, that peace of mind for terminally ill patients shouldn’t depend on whether they live in Oregon or not. Like Maynard, Jennifer Glass seems utterly brave and self-aware as she moves forward and, despite her disease, attempts to live a full life regardless of the harsh lesson mortality threatens to teach her. A few weeks shy of a late December CT scan to check for recurrence of her lung cancer, she said, “I feel fine now. But any minute things could go a different way. “My great hope is that, in the next 12 to 24 months, if my disease runs its course, then I will have the legal option to procure prescribed medicine and end my life, by my own choice, by my own hand, legally, in my own home.” And then, as if preparing for an upcoming debate, Glass posed a question to an imagined opponent of a California end-of-life choices law: “Nobody’s saying you have to do this if you don’t want to do it,” she said, “But who are you to say that I can’t?”How To Die in California

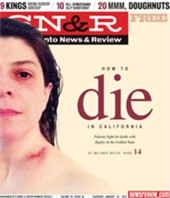

Brittany Maynard’s high-profile death may help usher in a right-to-die option for terminally ill patients in the Golden State